History Of Sacramento, California on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of Sacramento,

Sutter's empire began to disintegrate when he decided to back the unpopular Alta Californian governor

Sutter's empire began to disintegrate when he decided to back the unpopular Alta Californian governor

The real city of Sacramento was developed around a wharf, called the Embarcadero, on the confluence of the

The real city of Sacramento was developed around a wharf, called the Embarcadero, on the confluence of the

Those who sought land from 1848 onwards refused to honor the New Helvetian settlement and that Sutter alone held title to so much land; additionally, they refused to recognize the titles of

Those who sought land from 1848 onwards refused to honor the New Helvetian settlement and that Sutter alone held title to so much land; additionally, they refused to recognize the titles of

With the advent of the

With the advent of the

At the same time, the

At the same time, the  In 1920, Sacramento adopted a new charter government that dictated the creation of nine positions on a new

In 1920, Sacramento adopted a new charter government that dictated the creation of nine positions on a new  The events that followed World War I decreased the popularity for the reformist Progressive movement in the city; hundreds of Sacramentans joined the conservative local chapter

The events that followed World War I decreased the popularity for the reformist Progressive movement in the city; hundreds of Sacramentans joined the conservative local chapter

The

The

Sacramento's preeminent university,

Sacramento's preeminent university,  The Sacramento Kings National Basketball Association, NBA basketball franchise moved to Sacramento in 1985, and are currently Sacramento's only major professional sports team, though the city is home 2 professional minor league franchises, Sacramento Republic FC and the

The Sacramento Kings National Basketball Association, NBA basketball franchise moved to Sacramento in 1985, and are currently Sacramento's only major professional sports team, though the city is home 2 professional minor league franchises, Sacramento Republic FC and the

Discovery Museum's List of Famous People in Sacramento History

*

Sacramento History Online

*

*

*

Sacramento, California Usenet FAQs

*

{{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Sacramento, California History of Sacramento, California, Histories of cities in California, Sacramento

California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

, began with its founding by Samuel Brannan

Samuel Brannan (March 2, 1819 – May 5, 1889) was an American settler, businessman, journalist, and prominent Mormon who founded the '' California Star'', the first newspaper in San Francisco, California. He is considered the first to publici ...

and John Augustus Sutter, Jr. in 1848 around an embarcadero that his father, John Sutter, Sr. constructed at the confluence of the American

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

and Sacramento River

The Sacramento River ( es, Río Sacramento) is the principal river of Northern California in the United States and is the largest river in California. Rising in the Klamath Mountains, the river flows south for before reaching the Sacramento–S ...

s a few years prior.

Sacramento

)

, image_map = Sacramento County California Incorporated and Unincorporated areas Sacramento Highlighted.svg

, mapsize = 250x200px

, map_caption = Location within Sacramento ...

was named after the Sacramento River, which forms its western border. The river was named by Spanish cavalry officer Gabriel Moraga

Gabriel Moraga (1765 – June 14, 1823) was a Sonoran-born Californio explorer and army officer. He was the son of the expeditionary José Joaquín Moraga who helped lead the de Anza Expedition to California in 1774, Like his father, Moraga is on ...

for the Santisimo Sacramento (Most Holy Sacrament), referring to the Catholic Eucharist

The Eucharist (; from Greek , , ), also known as Holy Communion and the Lord's Supper, is a Christian rite that is considered a sacrament in most churches, and as an ordinance in others. According to the New Testament, the rite was instit ...

.

Before the arrival of Europeans, the Nisenan

The Nisenan are a group of Native Americans and an Indigenous people of California from the Yuba River and American River watersheds in Northern California and the California Central Valley. The Nisenan people are classified as part of the large ...

Native American tribe inhabited the Sacramento Valley

, photo =Sacramento Riverfront.jpg

, photo_caption= Sacramento

, map_image=Map california central valley.jpg

, map_caption= The Central Valley of California

, location = California, United States

, coordinates =

, boundaries = Sierra Nevada (ea ...

area. The Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Cana ...

were the first Europeans to explore the area, and Sacramento fell into the Alta California

Alta California ('Upper California'), also known as ('New California') among other names, was a province of New Spain, formally established in 1804. Along with the Baja California peninsula, it had previously comprised the province of , but ...

province of New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( es, Virreinato de Nueva España, ), or Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain during the Spanish colonization of the Am ...

when the conquistadors claimed Central America and the American Southwest for the Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire ( es, link=no, Imperio español), also known as the Hispanic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Hispánica) or the Catholic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Católica) was a colonial empire governed by Spain and its prede ...

. The area was deemed unfit for colonization by a number of explorers and as a result remained relatively untouched by the Europeans who claimed the region, excepting early 19th Century coastal settlements north of San Francisco Bay

San Francisco Bay is a large tidal estuary in the U.S. state of California, and gives its name to the San Francisco Bay Area. It is dominated by the big cities of San Francisco, San Jose, and Oakland.

San Francisco Bay drains water from a ...

which constituted the southernmost Russian colony in North America and were spread over an area stretching from Point Arena

Point Arena, formerly known as Punta Arena (Spanish language, Spanish for "Sandy Point") is a small coastal city in Mendocino County, California, Mendocino County, California, United States. Point Arena is located west of Hopland, California, H ...

to Tomales Bay

Tomales Bay is a long, narrow inlet of the Pacific Ocean in Marin County in northern California in the United States. It is approximately long and averages nearly wide, effectively separating the Point Reyes Peninsula from the mainland of Mar ...

.Historical Atlas of California When John Sutter

John Augustus Sutter (February 23, 1803 – June 18, 1880), born Johann August Sutter and known in Spanish as Don Juan Sutter, was a Swiss immigrant of Mexican and American citizenship, known for establishing Sutter's Fort in the area th ...

arrived in the provincial colonial capital of Monterey

Monterey (; es, Monterrey; Ohlone: ) is a city located in Monterey County on the southern edge of Monterey Bay on the U.S. state of California's Central Coast. Founded on June 3, 1770, it functioned as the capital of Alta California under both ...

in 1839, governor Juan Bautista Alvarado

Juan Bautista Valentín Alvarado y Vallejo (February 14, 1809 – July 13, 1882) was a Californio politician that served as Governor of Alta California from 1837-42. Prior to his term as governor, Alvarado briefly led a movement for independe ...

provided Sutter with the land he asked for, and Sutter established New Helvetia

New Helvetia (Spanish: Nueva Helvetia), meaning "New Switzerland", was a 19th-century Alta California settlement and Ranchos of California, rancho, centered in present-day Sacramento, California, Sacramento, California.

Colony of Nueva Helvetia

Th ...

, which he controlled absolutely with a private army and relative autonomy from the newly independent Mexican government.

The California Gold Rush

The California Gold Rush (1848–1855) was a gold rush that began on January 24, 1848, when gold was found by James W. Marshall at Sutter's Mill in Coloma, California. The news of gold brought approximately 300,000 people to California fro ...

started when gold was discovered at Sutter's Mill

Sutter's Mill was a water-powered sawmill on the bank of the South Fork American River in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada in California. It was named after its owner John Sutter. A worker constructing the mill, James W. Marshall, found gold t ...

, one of Sutter, Sr.'s assets in the city of Coloma in 1848; the arrival of prospectors in droves ruined Sutter's New Helvetia and trade began to develop around a wharf he had established where the American and Sacramento Rivers joined. In the region where Sutter had planned to establish the city of Sutterville, Sacramento City was founded; Sutter, Sr. put his son in charge in frustration, and Sutter, Jr. worked to organize the city in its growth. However, its location caused the city to periodically fill with water. Fires would also sweep through the city. To resolve the problems, the city worked to raise the sidewalks and buildings and began to replace wooden structures with more resilient materials, like brick and stone. The city was selected as the state capital in 1854 after Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo

Don Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo (4 July 1807 – 18 January 1890) was a Californio general, statesman, and public figure. He was born a subject of Spain, performed his military duties as an officer of the Republic of Mexico, and shaped the trans ...

failed to convince the state government to remain in the city of his namesake.

Prior to Sutter's arrival – through 1838

Indigenous people

Indigenous peoples are culturally distinct ethnic groups whose members are directly descended from the earliest known inhabitants of a particular geographic region and, to some extent, maintain the language and culture of those original people ...

such as the Miwok

The Miwok (also spelled Miwuk, Mi-Wuk, or Me-Wuk) are members of four linguistically related Native American groups indigenous to what is now Northern California, who traditionally spoke one of the Miwok languages in the Utian family. The word ' ...

and Maidu

The Maidu are a Native American people of northern California. They reside in the central Sierra Nevada, in the watershed area of the Feather and American rivers. They also reside in Humbug Valley. In Maiduan languages, ''Maidu'' means "man."

...

Indians were the original inhabitants of the north California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

n Central Valley. Of the Maidu, the Nisenan

The Nisenan are a group of Native Americans and an Indigenous people of California from the Yuba River and American River watersheds in Northern California and the California Central Valley. The Nisenan people are classified as part of the large ...

Maidu group were the principal inhabitants of pre-Columbian

In the history of the Americas, the pre-Columbian era spans from the original settlement of North and South America in the Upper Paleolithic period through European colonization, which began with Christopher Columbus's voyage of 1492. Usually, th ...

Sacramento; the peoples of this tribe were hunter-gatherer

A traditional hunter-gatherer or forager is a human living an ancestrally derived lifestyle in which most or all food is obtained by foraging, that is, by gathering food from local sources, especially edible wild plants but also insects, fungi, ...

s, relying on foraged nuts and berries and fish from local rivers instead of food generated by agricultural means.

The first European in the state of California was conquistador

Conquistadors (, ) or conquistadores (, ; meaning 'conquerors') were the explorer-soldiers of the Spanish and Portuguese Empires of the 15th and 16th centuries. During the Age of Discovery, conquistadors sailed beyond Europe to the Americas, O ...

Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo

''Juan'' is a given name, the Spanish and Manx versions of ''John''. It is very common in Spain and in other Spanish-speaking communities around the world and in the Philippines, and also (pronounced differently) in the Isle of Man. In Spanish, t ...

, a Portuguese

Portuguese may refer to:

* anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Portugal

** Portuguese cuisine, traditional foods

** Portuguese language, a Romance language

*** Portuguese dialects, variants of the Portuguese language

** Portu ...

explorer sailing on behalf of the Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire ( es, link=no, Imperio español), also known as the Hispanic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Hispánica) or the Catholic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Católica) was a colonial empire governed by Spain and its prede ...

, in 1542; later explorers included Sir Francis Drake

Sir Francis Drake ( – 28 January 1596) was an English explorer, sea captain, privateer, slave trader, naval officer, and politician. Drake is best known for his circumnavigation of the world in a single expedition, from 1577 to 1580 (t ...

and Sebastián Vizcaíno

Sebastián Vizcaíno (1548–1624) was a Spanish soldier, entrepreneur, explorer, and diplomat whose varied roles took him to New Spain, the Baja California peninsula, the California coast and Asia.

Early career

Vizcaíno was born in 154 ...

. However, no explorer had yet discovered the Sacramento Valley

, photo =Sacramento Riverfront.jpg

, photo_caption= Sacramento

, map_image=Map california central valley.jpg

, map_caption= The Central Valley of California

, location = California, United States

, coordinates =

, boundaries = Sierra Nevada (ea ...

region nor the Golden Gate

The Golden Gate is a strait on the west coast of North America that connects San Francisco Bay to the Pacific Ocean. It is defined by the headlands of the San Francisco Peninsula and the Marin Peninsula, and, since 1937, has been spanned by th ...

strait, which would remain undiscovered until, respectively, 1808 and 1623. A number of conquistadors had completed cursory examinations of the region by the mid-18th century, including Juan Bautista de Anza

Juan Bautista de Anza Bezerra Nieto (July 6 or 7, 1736 – December 19, 1788) was an expeditionary leader, military officer, and politician primarily in California and New Mexico under the Spanish Empire. He is credited as one of the founding fa ...

and Pedro Fages

Pedro Fages (1734–1794) was a Spanish soldier, explorer, first Lieutenant Governor of the Californias under Gaspar de Portolá. Fages claimed the governorship after Portolá's death, acting as governor in opposition to the official governor ...

, but none viewed the region as a potentially valuable region to colonize. Neither did Gabriel Moraga

Gabriel Moraga (1765 – June 14, 1823) was a Sonoran-born Californio explorer and army officer. He was the son of the expeditionary José Joaquín Moraga who helped lead the de Anza Expedition to California in 1774, Like his father, Moraga is on ...

, who was the first European to enter the Sierra in 1808 and was responsible for naming the Sacramento River

The Sacramento River ( es, Río Sacramento) is the principal river of Northern California in the United States and is the largest river in California. Rising in the Klamath Mountains, the river flows south for before reaching the Sacramento–S ...

, although he incorrectly placed the rivers in the region. However, Padres Abella and Fortuni arrived in the region in 1811 and returned positive feedback to the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, although the church disregarded their finds as they were in conflict with all previous views of the area. The Mexicans

Mexicans ( es, mexicanos) are the citizens of the United Mexican States.

The most spoken language by Mexicans is Spanish language, Spanish, but some may also speak languages from 68 different Languages of Mexico, Indigenous linguistic groups ...

, who had declared independence in 1821, shared Spanish sentiments,Severson, p. 21 and the area remained uncolonized until the arrival of John Sutter in 1839.

The area that would become the city of Sacramento was initially observed by many European and American mapmakers as home to Great Plains

The Great Plains (french: Grandes Plaines), sometimes simply "the Plains", is a broad expanse of flatland in North America. It is located west of the Mississippi River and east of the Rocky Mountains, much of it covered in prairie, steppe, an ...

-based rivers that stretched across the Rocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in straight-line distance from the northernmost part of western Canada, to New Mexico in ...

and emptied into the Pacific Ocean. Speculation at the time placed the fabled St. Bonaventura River where the American

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

-Sacramento River

The Sacramento River ( es, Río Sacramento) is the principal river of Northern California in the United States and is the largest river in California. Rising in the Klamath Mountains, the river flows south for before reaching the Sacramento–S ...

complex was; mountain man

A mountain man is an explorer who lives in the wilderness. Mountain men were most common in the North American Rocky Mountains from about 1810 through to the 1880s (with a peak population in the early 1840s). They were instrumental in opening up ...

Jedediah Smith

Jedediah Strong Smith (January 6, 1799 – May 27, 1831) was an American clerk, transcontinental pioneer, frontiersman, hunter, trapper, author, cartographer, mountain man and explorer of the Rocky Mountains, the Western United States, and ...

mistook the American and Sacramento Rivers for the St. Bonaventura in his 1827 venture into the region, and named the Sacramento Valley the "Valley of the Bonadventure" before trekking southwards along the Stanislaus River

The Stanislaus River is a tributary of the San Joaquin River in north-central California in the United States. The main stem of the river is long, and measured to its furthest headwaters it is about long. Originating as three forks in the high ...

.

Mexican Territory: Sutter's Colony – 1839 to 1848

John Augustus Sutter

John Augustus Sutter (February 23, 1803 – June 18, 1880), born Johann August Sutter and known in Spanish as Don Juan Sutter, was a Swiss immigrant of Mexican and American citizenship, known for establishing Sutter's Fort in the area ...

arrived in the city of Yerba Buena

Yerba buena or hierba buena is the Spanish name for a number of aromatic plants, most of which belong to the mint family. ''Yerba buena'' translates as "good herb". The specific plant species regarded as ''yerba buena'' varies from region to regi ...

, which would become the city of San Francisco, after encountering a massive storm en route from the city of Sitka

russian: Ситка

, native_name_lang = tli

, settlement_type = Consolidated city-borough

, image_skyline = File:Sitka 84 Elev 135.jpg

, image_caption = Downtown Sitka in 1984

, image_size ...

, Russian Alaska

Russian America (russian: Русская Америка, Russkaya Amerika) was the name for the Russian Empire's colonial possessions in North America from 1799 to 1867. It consisted mostly of present-day Alaska in the United States, but a ...

; he was later redirected by Mexican officials to the colonial capital of Monterey

Monterey (; es, Monterrey; Ohlone: ) is a city located in Monterey County on the southern edge of Monterey Bay on the U.S. state of California's Central Coast. Founded on June 3, 1770, it functioned as the capital of Alta California under both ...

, where he appealed to governor Juan Bautista Alvarado

Juan Bautista Valentín Alvarado y Vallejo (February 14, 1809 – July 13, 1882) was a Californio politician that served as Governor of Alta California from 1837-42. Prior to his term as governor, Alvarado briefly led a movement for independe ...

of Alta California

Alta California ('Upper California'), also known as ('New California') among other names, was a province of New Spain, formally established in 1804. Along with the Baja California peninsula, it had previously comprised the province of , but ...

his ambitions to establish an "empire of civilization" on "new land". Alvarado noted that he needed to establish a presence in the Sacramento Valley, and realized that Sutter's ambitions allowed him an opportunity to secure the valley without committing extra troops to the region. As a result, he granted Sutter's requestSeverson, p. 30 on the condition that Sutter would become a Mexican citizen. Sutter commenced to build a fort of his namesake, Sutter's Fort

Sutter's Fort was a 19th-century agricultural and trade colony in the Mexican ''Alta California'' province.National Park Service"California National Historic Trail."/ref> The site of the fort was established in 1839 and originally called New Helve ...

, in 1840; the fort became his base of operations. New Helvetia was roughly in size until he negotiated an 1841 deal with the Russians to purchase Ft. Ross, which lay in present-day Sonoma County

Sonoma County () is a county (United States), county located in the U.S. state of California. As of the 2020 United States Census, its population was 488,863. Its county seat and largest city is Santa Rosa, California, Santa Rosa. It is to the n ...

, and consolidated all of Ft. Ross' holdings with those at Fort Sutter.Severson, p. 34

Sutter's New Helvetia existed within Mexican borders, sporting a large degree of autonomy

In developmental psychology and moral, political, and bioethical philosophy, autonomy, from , ''autonomos'', from αὐτο- ''auto-'' "self" and νόμος ''nomos'', "law", hence when combined understood to mean "one who gives oneself one's ...

; John Sutter ruled over New Helvetia with absolute power, and named himself general over a privately developed army

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

composed of Native Americans. John Sutter employed both white people and Native Americans for many mundane and military tasks regarding New Helvetia. After New Helvetia grew to encompass Fort Ross, Sutter's military presence in the region began to garner suspicion from the government of Mexican Alta California; Sutter, who often bragged of his military strength, aggravated the Mexican government with his claims of power. As New Helvetia continued to develop economically, Sutter constructed a ranch at the Nisenan village of Hok and named it " Hock Farm", designating it his official retreat. New Helvetia was considered a stable colony by 1844, and was the only foreigner-friendly locale in Alta California at the time. Among other foreigners, the Donner Party

The Donner Party, sometimes called the Donner–Reed Party, was a group of American pioneers who migrated to California in a wagon train from the Midwest. Delayed by a multitude of mishaps, they spent the winter of 1846–1847 snowbound in th ...

had designated Sutter's Fort their destination during an overland journey that placed them across the Sierra mountains in the wintertime.

Sutter's empire began to disintegrate when he decided to back the unpopular Alta Californian governor

Sutter's empire began to disintegrate when he decided to back the unpopular Alta Californian governor Manuel Micheltorena

Joseph Manuel María Joaquin Micheltorena y Llano (8 June 1804 – 7 September 1853) was a brigadier general of the Mexican Army, adjutant-general of the same, governor, commandant-general and inspector of the department of Las Californias, then ...

, who was soon overthrown by Alvarado and José Castro

José Antonio Castro (1808 – February 1860) was a Californio politician, statesman, and general who served as interim Governor of Alta California and later Governor of Baja California. During the Bear Flag Revolt and the American Conquest of ...

in an 1841 coup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, m ...

. Sutter was jailed as a result, but not before Micheltorena issued the Sobrante Grant, which added of land to New Helvetian territory. In 1845, Castro arrived at Sutter's Fort and offered a deal to purchase New Helvetia; Sutter declined, although he later expressed regret for not accepting Castro's terms. In 1846, the Bear Flag Revolt

The California Republic ( es, La República de California), or Bear Flag Republic, was an unrecognized breakaway state from Mexico, that for 25 days in 1846 militarily controlled an area north of San Francisco, in and around what is now Son ...

was initiated by Americans in Sonoma who were frightened by growing Mexican hostility towards foreign presences in the region; taking the city by surprise, general Mariano Vallejo

Don Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo (4 July 1807 – 18 January 1890) was a Californio general, statesman, and public figure. He was born a subject of Spain, performed his military duties as an officer of the Republic of Mexico, and shaped the transi ...

was captured at his headquarters in the city, and the irregular force demanded use of Sutter's prison facilities to host captured Mexican officials. Agreeing reluctantly, Sutter raised the Bear Flag

The Bear Flag is the official flag of the U.S. state of California. The precursor of the flag was first flown during the 1846 Bear Flag Revolt and was also known as the Bear Flag. A predecessor, called the Lone Star Flag, was used in an 183 ...

over his fortification. However, he treated the Vallejos, whom he considered friends, as guests and not as prisoners. While the "Bear Flaggers" under William B. Ide

William Brown Ide (March 28, 1796 – December 19 or 20, 1852) was an American pioneer who headed the short-lived California Republic in 1846.

Life

William Ide was born in Rutland, Massachusetts to Lemuel Ide, a member of the Vermont State Legi ...

and John C. Frémont

John Charles Frémont or Fremont (January 21, 1813July 13, 1890) was an American explorer, military officer, and politician. He was a U.S. Senator from California and was the first Republican nominee for president of the United States in 1856 ...

continued to wage war against the Mexican government, Sutter attempted to resume a state of normalcy in New Helvetia, although the lack of manpower as a result of the revolt left productivity lagging.

The United States initiated the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1 ...

in 1846 against Mexico in the wake of the U.S. annexation

Annexation (Latin ''ad'', to, and ''nexus'', joining), in international law, is the forcible acquisition of one state's territory by another state, usually following military occupation of the territory. It is generally held to be an illegal act ...

of the Republic of Texas

The Republic of Texas ( es, República de Tejas) was a sovereign state in North America that existed from March 2, 1836, to February 19, 1846, that bordered Mexico, the Republic of the Rio Grande in 1840 (another breakaway republic from Mex ...

, whose independence Mexico had not recognized. California, along with Nevada, Utah, New Mexico, most of Arizona and Colorado, and parts of Oklahoma, Kansas, and Wyoming, were annexed by the United States in the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ( es, Tratado de Guadalupe Hidalgo), officially the Treaty of Peace, Friendship, Limits, and Settlement between the United States of America and the United Mexican States, is the peace treaty that was signed on 2 ...

. Thus, Sutter's New Helvetia fell under U.S. control.

Continuing business as normal, John Sutter dispatched associate James W. Marshall

James Wilson Marshall (October 8, 1810 – August 10, 1885) was an American carpenter and sawmill operator, who on January 24, 1848 reported the finding of gold at Coloma, California, a small settlement on the American River about 36 miles no ...

, who was to construct a sawmill

A sawmill (saw mill, saw-mill) or lumber mill is a facility where logs are cut into lumber. Modern sawmills use a motorized saw to cut logs lengthwise to make long pieces, and crosswise to length depending on standard or custom sizes (dimensi ...

in the foothills of the Sierra at the city of Coloma, in 1847. In January 1848, Marshall detected a flake of gold on the ground at the site of Sutter's new mill, and after conducting tests, determined the mineral's authenticity. Word leaked about the discovery nearly immediately. When news reached San Francisco, a rush of hopeful prospectors began to move northwards to the Sacramento Valley, and by the middle of the year, so-called "Argonauts

The Argonauts (; Ancient Greek: ) were a band of heroes in Greek mythology, who in the years before the Trojan War (around 1300 BC) accompanied Jason to Colchis in his quest to find the Golden Fleece. Their name comes from their ship, '' Argo'', ...

" flooded Sutter's holdings in search of gold. The arrival of Argonauts in the region decimated the economical integrity of Sutter's New Helvetia, as the prospectors slaughtered his herds of livestock, drove out local Native Americans loyal to Sutter, and divided New Helvetia amongst each other without Sutter's consent. Disappointed with what had become of his holdings, Sutter placed his son as head of fort business operations and retired to Hock Farm.

Foundation – 1848 to 1850

The real city of Sacramento was developed around a wharf, called the Embarcadero, on the confluence of the

The real city of Sacramento was developed around a wharf, called the Embarcadero, on the confluence of the American River

, name_etymology =

, image = American River CA.jpg

, image_size = 300

, image_caption = The American River at Folsom

, map = Americanrivermap.png

, map_size = 300

, map_caption ...

and Sacramento River

The Sacramento River ( es, Río Sacramento) is the principal river of Northern California in the United States and is the largest river in California. Rising in the Klamath Mountains, the river flows south for before reaching the Sacramento–S ...

that Sutter had developed prior to his retirement in 1849 as a result of gold discoveries at Sutter's Mill

Sutter's Mill was a water-powered sawmill on the bank of the South Fork American River in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada in California. It was named after its owner John Sutter. A worker constructing the mill, James W. Marshall, found gold t ...

in Coloma.Severson, p. 51 John Sutter, Sr. had replaced himself with his son, John Sutter, Jr.

John Augustus Sutter Jr. (October 25, 1826 – September 21, 1897) was the founder and planner of the City of Sacramento in California, a U.S. Consul in Acapulco, Mexico and the son of German-born but Swiss-raised American pioneer John August ...

, who noticed growth of trade at the Embarcadero and considered it a viable economic opportunity; the port was used increasingly as a point of debarkation for prospecting Argonauts heading eastwards. Sutter, Jr. had military officials William H. Warner and his assistant, William Tecumseh Sherman

William Tecumseh Sherman ( ; February 8, 1820February 14, 1891) was an American soldier, businessman, educator, and author. He served as a general in the Union Army during the American Civil War (1861–1865), achieving recognition for his com ...

, survey his father's holdings for a location where he could establish a new city and create the city over a grid of numbered and lettered streets for organizational purposes. A number of businessmen, including millionaire-to-be Samuel Brannan

Samuel Brannan (March 2, 1819 – May 5, 1889) was an American settler, businessman, journalist, and prominent Mormon who founded the '' California Star'', the first newspaper in San Francisco, California. He is considered the first to publici ...

, future California governor Peter Burnett

Peter Hardeman Burnett (November 15, 1807May 17, 1895) was an American politician who served as the first elected Governor of California from December 20, 1849, to January 9, 1851. Burnett was elected Governor almost one year before California's ...

, and George McDougall

George Millward McDougall (September 9, 1821 – January 25, 1876) was a Methodist missionary in Canada who assisted in negotiations leading to Treaty 6 and Treaty 7 between the Canadian government and the Indian tribes of western Canada. He was ...

, brother of future California governor John McDougall, were attracted to the waterfront location. However, Sutter, Jr. and George McDougall disagreed over the terms of the lease of the location, and a trade war erupted between Sutter's Sacramento City and McDougall's new base of operations at Sutterville. Sutter, Sr., who had opposed many of his son's decisions, resumed control of his business affairs after Sutter, Jr. ended the competition between the two cities; trade in the area was biased toward Sacramento City as a result of Sutter, Jr.'s efforts.Severson, p. 52

Unlike other settlements of its time and type, Sacramento City did not have gambling houses and saloons until the summer of 1849; the city was free of those businesses for the first few months of its existence. Churches also appeared early on when the Methodist Episcopal

The Methodist Episcopal Church (MEC) was the oldest and largest Methodist denomination in the United States from its founding in 1784 until 1939. It was also the first religious denomination in the US to organize itself on a national basis. In ...

ian pastor W. Grove Deal established the first church with regular services in May 1849. Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

reverend Augustine Anderson arrived in 1850 and constructed a church in 1854, while Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

founded a synagogue

A synagogue, ', 'house of assembly', or ', "house of prayer"; Yiddish: ''shul'', Ladino: or ' (from synagogue); or ', "community". sometimes referred to as shul, and interchangeably used with the word temple, is a Jewish house of worshi ...

called Congregation B'Nai Israel in 1852. In 1849, Edward C. Kemble moved north from San Francisco and established the city's first newspaper, ''The Placer Times''. Kemble's newspaper disassembled three months later when Kemble was stricken with sickness. The first Sacramento theatrical stage, located in the Eagle Theatre (Sacramento, California)

The Eagle Theatre in Gold Rush-era Sacramento was the first permanent theatre to be built in the state of California. Established in 1849 this relatively small structure was originally wood-framed and canvas-covered with a tin roof and a packed ear ...

, was founded in October 1849.

Sacramento City did not have a formal government during early and mid-1849, and gambling institutions in the region sought to keep only the loose alcalde

Alcalde (; ) is the traditional Spanish municipal magistrate, who had both judicial and administrative functions. An ''alcalde'' was, in the absence of a corregidor, the presiding officer of the Castilian '' cabildo'' (the municipal council) a ...

government. However, many city residents were swayed in favor of the gambling houses; by the fall of that year, the entire legal structure of Sacramento City was established by a large 296-vote margin on a second proposal. The government of California had only just reorganized itself into county

A county is a geographic region of a country used for administrative or other purposesChambers Dictionary, L. Brookes (ed.), 2005, Chambers Harrap Publishers Ltd, Edinburgh in certain modern nations. The term is derived from the Old French ...

units; days after the overhaul, the California State Legislature

The California State Legislature is a bicameral state legislature consisting of a lower house, the California State Assembly, with 80 members; and an upper house, the California State Senate, with 40 members. Both houses of the Legisla ...

verified that Sacramento was officially recognized by means of charter

A charter is the grant of authority or rights, stating that the granter formally recognizes the prerogative of the recipient to exercise the rights specified. It is implicit that the granter retains superiority (or sovereignty), and that the rec ...

in February 1850. Sacramento City later petitioned the Legislature to drop the "City" from the settlement's name, which was also granted. Sacramento City was serviced by organized public transportation via the rivers and upheld regular street maintenance by 1850; the settlement had reached a "home-and-garden" stage in development by the same time.

Early development – 1850 to 1860

In January 1850, a major flood devastated the city. Rain from heavy storms had saturated the grounds upon which Sacramento was built, and the American and Sacramento rivers crested simultaneously. The economic impact was significant because merchandise stationed at the Embarcadero was not secured and washed away in the flood. Sacramento rallied behindHardin Bigelow

Hardin Bigelow (1809 in Michigan Territory – November 27, 1850 in San Francisco, California) was the first elected mayor of the city of Sacramento, California, which was known then as "Sacramento City." Bigelow's efforts to construct Sac ...

, who led efforts to implement emergency measures to protect the city from another disaster of that nature. Responsibility for construction of protective levees and dams won him support, and he was elected first mayor of the city.

A second major flood in March 1850 was averted by Bigelow's efforts.Severson, p. 73 In April of the same year, the city experienced its first major fire. A second fire in November destroyed a number of commercial establishments in the city. In response to growing fear of a potential catastrophe, citizen volunteers founded California's first fire protection

Fire protection is the study and practice of mitigating the unwanted effects of potentially destructive fires. It involves the study of the behaviour, compartmentalisation, suppression and investigation of fire and its related emergencies, as we ...

organization, named the "Mutual Hook and Ladder Company." The city adapted by implementing iron window shutters

A window shutter is a solid and stable window covering usually consisting of a frame of vertical stiles and horizontal rails (top, centre and bottom). Set within this frame can be louvers (both operable or fixed, horizontal or vertical), solid ...

to reduce wind draft and make fires harder to spread.

October 1850 brought the arrival of the ''New World'', a riverboat that carried news of California's admittance to the Union

In electrical engineering, admittance is a measure of how easily a circuit or device will allow a current to flow. It is defined as the reciprocal of impedance, analogous to how conductance & resistance are defined. The SI unit of admittance ...

.Severson, p. 79 It also brought the cholera epidemic

Seven cholera pandemics have occurred in the past 200 years, with the first pandemic originating in India in 1817. The seventh cholera pandemic is officially a current pandemic and has been ongoing since 1961, according to a World Health Organizat ...

that killed between 800 and 1,000 people within three weeks including between a quarter to half of the city's physicians. Nearly eighty percent of the population fled.Flynn, p. 67 Bodies were buried in mass graves

A mass grave is a grave containing multiple human corpses, which may or may not be identified prior to burial. The United Nations has defined a criminal mass grave as a burial site containing three or more victims of execution, although an exact ...

at cemeteries across the city.

Those who sought land from 1848 onwards refused to honor the New Helvetian settlement and that Sutter alone held title to so much land; additionally, they refused to recognize the titles of

Those who sought land from 1848 onwards refused to honor the New Helvetian settlement and that Sutter alone held title to so much land; additionally, they refused to recognize the titles of speculators

In finance, speculation is the purchase of an asset (a commodity, goods, or real estate) with the hope that it will become more valuable shortly. (It can also refer to short sales in which the speculator hopes for a decline in value.)

Many s ...

who sold the land at exorbitant prices. The squatters

Squatting is the action of occupying an abandoned or unoccupied area of land or a building, usually residential, that the squatter does not own, rent or otherwise have lawful permission to use. The United Nations estimated in 2003 that there ...

who wished to take from Sutter's land worked to find loopholes in the law that would allow them to claim the land as public and render his, and those of the speculators that bought land from him, invalid. The push for recognition of squatter's rights

Adverse possession, sometimes colloquially described as "squatter's rights", is a legal principle in the Anglo-American common law under which a person who does not have legal title to a piece of property—usually land ( real property)—may ...

in the Sacramento area led to the formation of a Law and Order Association amongst the squatters. When a squatter was judged for execution and was denied passage to a squatters' appeals court, the squatters swore that they were prepared for warfare in the case that their claims were denied judgment by higher courts. Rallying under future Kansas governor Charles L. Robinson

Charles Lawrence Robinson (July 21, 1818 – August 17, 1894) was an American politician who served in the California State Assembly from 1851-52, and later as the first Governor of Kansas from 1861 until 1863. He was also the first governor o ...

, the squatters formed militias and prepared to attack the city; however, Hardin Bigelow averted the crisis temporarily by assuring the squatters that arrests will not be made as a result of siding with Robinson. However, violence finally broke out when Bigelow moved to stop Robinson from freeing prisoners held captive aboard the prison brig, the ''La Grange'', on August 14, 1850. Bigelow repelled the force at the cost of his health. The Sheriff, McKinney, moved to attack a retreat near the settlement of Brighton just outside city limits; McKinney and three squatters died, but the event, which came to be known as the Squatters Riot

The Squatters' riot was an uprising and conflict that took place between squatting settlers and the government of Sacramento, California, Sacramento, California (then an unorganized territory annexed after the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo) in Augus ...

, drew to a close.Severson, p. 79 Additionally, the year afterwards, a group of 213 Sacramentans founded the extralegal Vigilance Committee after the group of the same name and purpose in the San Francisco Bay Area

The San Francisco Bay Area, often referred to as simply the Bay Area, is a populous region surrounding the San Francisco, San Pablo, and Suisun Bay estuaries in Northern California. The Bay Area is defined by the Association of Bay Area Go ...

; lynching

Lynching is an extrajudicial killing by a group. It is most often used to characterize informal public executions by a mob in order to punish an alleged transgressor, punish a convicted transgressor, or intimidate people. It can also be an ex ...

a prisoner who was pardon

A pardon is a government decision to allow a person to be relieved of some or all of the legal consequences resulting from a criminal conviction. A pardon may be granted before or after conviction for the crime, depending on the laws of the ju ...

ed by the mayor of the city, the committee dissolved soon afterwards, losing support after demanding that the mayor step down for interfering needlessly and when the mayor refused to do so.

By 1852, Sutter's New Helvetia had collapsed completely, and Sutter's Fort had been abandoned. Sacramento's commerce had become reliant on coins, and the city had outgrown its unstable Gold Rush boomtown

A boomtown is a community that undergoes sudden and rapid population and economic growth, or that is started from scratch. The growth is normally attributed to the nearby discovery of a precious resource such as gold, silver, or oil, although ...

status and established itself as a fully fledged community; The Embarcadero, which had driven the growth of Sacramento from the start, no longer solely determined if the city would survive or be abandoned. The year 1852 saw a diversification in the Sacramentan economy; pharmacies, attorney firms, brass foundries, and lingerie shops, among others, lined the streets of the city during this era. Additionally, companies were beginning to take advantage of the fish populations in the American and Sacramento Rivers, a resource that Sutter had discovered and utilized during the era of New Helvetia. The Central Valley's capacity for agriculture was also noted, and wheat surpluses that had originated in the Sacramento area were often shipped en route to foreign countries. However, the city caught afire the night of November 2, 1852; nearly 85% of the city was destroyed in the fire. Sacramentans rebuilt the city with brick, rather than the fire-hazardous wood that was the medium for buildings in that era. A second fire in 1854 destroyed twelve newly reconstructed downtown city blocks, including the city courthouse.Severson, p. 107

The American state of California's government met in Monterey

Monterey (; es, Monterrey; Ohlone: ) is a city located in Monterey County on the southern edge of Monterey Bay on the U.S. state of California's Central Coast. Founded on June 3, 1770, it functioned as the capital of Alta California under both ...

in late 1849, the capital of the former Alta California, to conduct the first State Constitutional Convention; the seat of government was set in San Jose, although the government disliked the locale. Former Mexican general Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo

Don Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo (4 July 1807 – 18 January 1890) was a Californio general, statesman, and public figure. He was born a subject of Spain, performed his military duties as an officer of the Republic of Mexico, and shaped the trans ...

promised a viable capital city at Vallejo in 1852. Vallejo was unable to sufficiently construct the city of Vallejo, and the government was moved to the city of Sacramento temporarily; after Vallejo failed again, he released himself from his contract to the state, and the government moved to Benicia

Benicia ( , ) is a waterside city in Solano County, California, located in the North Bay region of the San Francisco Bay Area. It served as the capital of California for nearly thirteen months from 1853 to 1854. The population was 26,997 at the ...

until Sacramento made a bid for the capital that the Legislature accepted completely in 1854. The same year, the state legislature voted to make Sacramento the permanent state capital. Construction on the California State Capitol

The California State Capitol is the seat of the California state government, located in Sacramento, the state capital of California. The building houses the chambers of the California State Legislature, made up of the Assembly and the Senate, al ...

commenced in 1860; the structure would take fourteen years to complete.

In early 1855, Colonel Charles L. Wilson and Theodore Judah

Theodore Dehone Judah (March 4, 1826 – November 2, 1863) was an American civil engineer who was a central figure in the original promotion, establishment, and design of the First transcontinental railroad. He found investors for what became th ...

started work on the Sacramento Valley Railroad; the railroad was the first to be chartered west of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

and was done so by Colonel Wilson three years prior. A money panic caused by an unfavorable winter forced Wilson to retire from the project, and he was replaced by Joseph Libbey Folsom; Folsom died in July and was replaced by C. K. Garrison. As ongoing difficulties for the project continued to hinder operations, the length of the railroad was limited to the city of Granite City (later renamed for Folsom), twenty-two miles away.Severson, p. 171 After Judah completed the track for the Sacramento Valley Railroad in 1856, he petitioned the U.S. government for a transcontinental railroad. However, tensions over slavery between pro-slavery

Proslavery is a support for slavery. It is found in the Bible, in the thought of ancient philosophers, in British writings and in American writings especially before the American Civil War but also later through 20th century. Arguments in favor o ...

and anti-slavery

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The Britis ...

forces in the east took precedence over Judah's proposition.

The Civil War era to the twentieth century – 1861 to 1900

TheCalifornia Republican Party

The California Republican Party (CAGOP) is the affiliate of the United States Republican Party in the U.S. state of California. The party is based in Sacramento and is led by chair Jessica Millan Patterson.

As of October 2020, Republicans repre ...

was founded in Sacramento on April 18, 1856, when the first mass meeting aggregated in the city. When the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

started, the city was strongly pro-Union, although the opposing side, the Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America (CSA), commonly referred to as the Confederate States or the Confederacy was an unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United States that existed from February 8, 1861, to May 9, 1865. The Confeder ...

, had active supporters within the city. The city of Sacramento's population was alarmed at the possibility of an invasion by forces that were stationed in Confederate Texas

Texas declared its secession from the Union on February 1, 1861, and joined the Confederate States on March 2, 1861, after it had replaced its governor, Sam Houston, who had refused to take an oath of allegiance to the Confederacy. As with t ...

when the Union presence stationed within the city was drawn eastwards for battle. As a result, volunteers organized into military defense forces in case an invasion ever would take place.

As a means of communication meant to replace the inefficient letter delivery via ocean around South America's Cape Horn

Cape Horn ( es, Cabo de Hornos, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which are the Diego Ramírez ...

, the Pony Express

The Pony Express was an American express mail service that used relays of horse-mounted riders. It operated from April 3, 1860, to October 26, 1861, between Missouri and California. It was operated by the Central Overland California and Pik ...

was brought to Sacramento in 1860. This was the first cross-continent means of communication and tied California to the states in the east across the Great Plains. However, the Pony Express only lasted eighteen months and was rendered obsolete upon the arrival of the First Transcontinental Telegraph

The first transcontinental telegraph (completed October 24, 1861) was a line that connected the existing telegraph network in the eastern United States to a small network in California, by means of a link between Omaha, Nebraska and Carson City, ...

.Severson, p. 182-183 By 1861, Sacramento was linked to the telegraph lines on the other side of the continent.

December 1861 and January 1862 brought about devastating floods that placed the future of the city in doubt. In order to resolve the situation, the city residents agreed that additional levee construction was necessary. However, the city was divided between camps that supported a relatively small grading of a few feet to raise the city just above the rivers' cresting levels and those that supported a substantial grading to accommodate basements in city businesses. In the upcoming election of 1863, the level at which the city should be raised became a primary factor; a candidate that supported high-level grading won, and high-level grading renovation proceeded. Earth was removed from a dangerous bend nearby the confluence of the two rivers and used to raise city blocks in 1868; the city's sidewalks, until construction was finally finished, were uneven because neighbors of raised city blocks often remained at the pre-construction level. After the filled regions beneath buildings had settled, new streets had to be paved. While planking had been used in the past, newly raised streets chose either the smooth (though undurable) Nicolson pavement

Nicolson pavement, alternatively spelled "Nicholson" and denominated wooden block pavement and wood block pavement, is a road surface material consisting of wooden blocks. Samuel Nicolson invented it in the mid-19th century. Wooden block pavemen ...

or the easily dirtied (though durable) cobblestone

Cobblestone is a natural building material based on cobble-sized stones, and is used for pavement roads, streets, and buildings.

Setts, also called Belgian blocks, are often casually referred to as "cobbles", although a sett is distinct fro ...

pavement. Grading and paving processes were fully completed by 1873, leaving the first floors of many buildings at the time as basements and leaving second floors as new main floors. Today, this system of 19th-century basements is known as the Sacramento Underground.

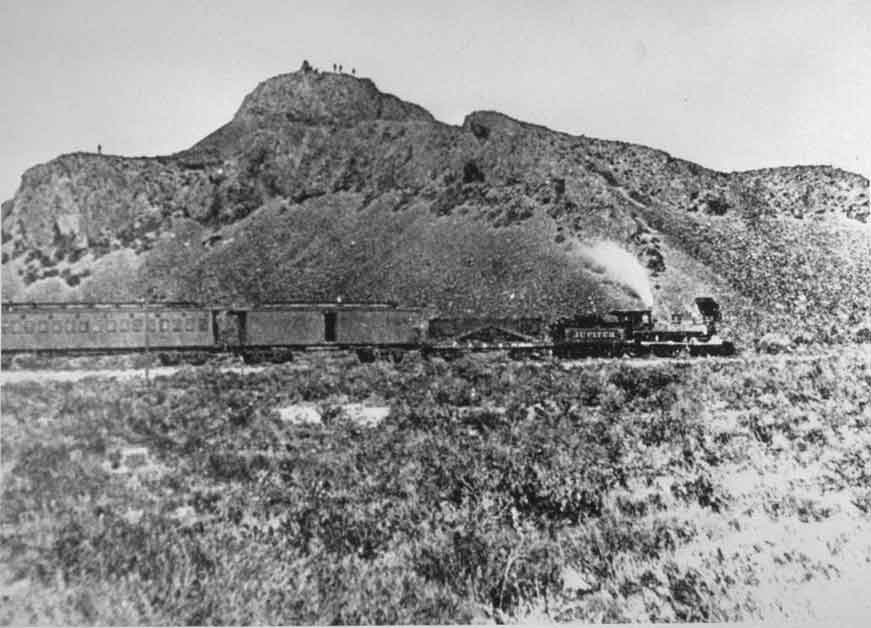

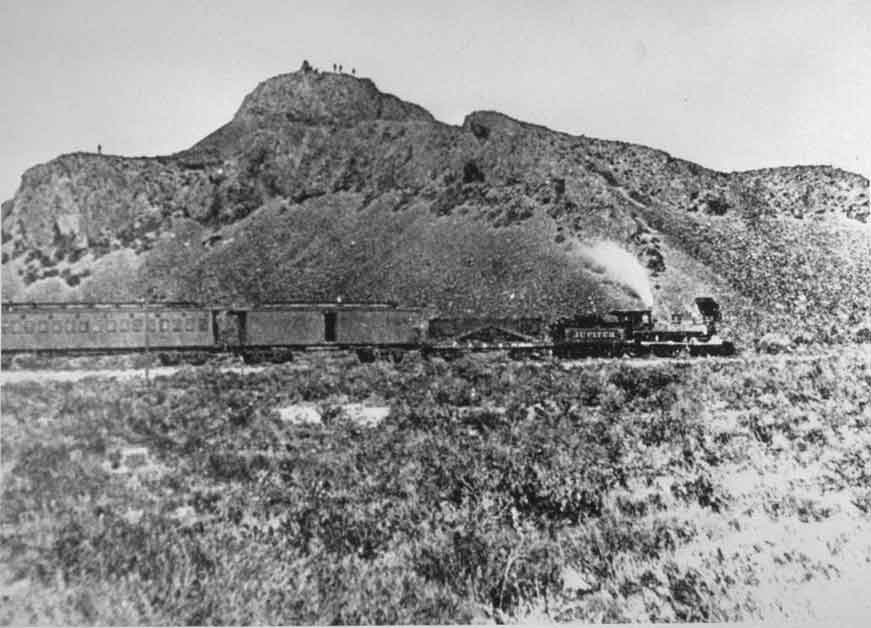

While the grading of the city commenced, Theodore Judah, who continued to request government grants in an attempt to build a transcontinental railroad, did not receive the reception he wished; instead, he worked with Daniel Strong and generated the Central Pacific Railroad

The Central Pacific Railroad (CPRR) was a rail company chartered by Pacific Railroad Acts, U.S. Congress in 1862 to build a railroad eastwards from Sacramento, California, to complete the western part of the "First transcontinental railroad" in N ...

plan. However, the Sacramento Valley Railroad ejected him from its administration, suspicious of his actions. For matters of funding, Judah met with thirty Sacramento businessmen and discussed the possibility of this railroad. Among those businessmen were '' the Big Four'': Mark Hopkins, Jr.

Mark Hopkins Jr. (September 1, 1813 – March 29, 1878) was an American railroad executive. He was one of four principal investors that funded Theodore D. Judah's idea of building a railway over the Sierra Nevada from Sacramento, California ...

, Charles Crocker

Charles Crocker (September 16, 1822 – August 14, 1888) was an American railroad executive who was one of the founders of the Central Pacific Railroad, which constructed the westernmost portion of the first transcontinental railroad, and took ...

, Collis P. Huntington

Collis Potter Huntington (October 22, 1821 – August 13, 1900) was an American industrialist and railway magnate. He was one of the Big Four of western railroading (along with Leland Stanford, Mark Hopkins, and Charles Crocker) who invested ...

, and Leland Stanford

Amasa Leland Stanford (March 9, 1824June 21, 1893) was an American industrialist and politician. A member of the Republican Party, he served as the 8th governor of California from 1862 to 1863 and represented California in the United States Se ...

. Together, the four formed the Central Pacific Railroad of California in 1861. The American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

began, and president Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

approved the railroad without the Southern forces that would've normally opposed the operation; ground was broken in downtown Sacramento on January 8, 1863. By 1865, the burgeoning company absorbed the Sacramento Valley Railroad, and the original Western Pacific Railroad was purchased in 1867, which was incorporated to connect Sacramento to Stockton. The California Pacific Railroad

The California Pacific Railroad Company (abbreviated Cal. P. R. R. or Cal-P) was incorporated in 1865 at San Francisco, California as the California Pacific ''Rail Road'' Company. It was renamed the California Pacific Railroad ''Extension'' Compan ...

Company in 1868 initiated a "war" with the Central Pacific Railroad over control of Sacramento, involving legal and extralegal action. As a result of the endeavors taken between the two railroad companies, the Yolo-Sacramento Bridge was created, the first bridge across the Sacramento river. The "war" ended when the California Pacific Railroad was absorbed into the Central Pacific Railroad Company. The dominance of railroad companies prevailed in Sacramento during this part of its history; mayor William Land, who served in 1898–99, was considered a pawn of the railroad companies, and Southern Pacific Railroad Company

The Southern Pacific (or Espee from the railroad initials- SP) was an American Class I railroad network that existed from 1865 to 1996 and operated largely in the Western United States. The system was operated by various companies under the ...

executive William Herrin often dodged attempts at reform and bent public policy to better serve his railroad.

With the advent of the

With the advent of the railroad

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport that transfers passengers and goods on wheeled vehicles running on rails, which are incorporated in tracks. In contrast to road transport, where the vehicles run on a pre ...

and the introduction of refrigeration

The term refrigeration refers to the process of removing heat from an enclosed space or substance for the purpose of lowering the temperature.International Dictionary of Refrigeration, http://dictionary.iifiir.org/search.phpASHRAE Terminology, ht ...

, wheat prices dropped, and fruit became a significant cash crop. As a result, in 1883 onwards until the start of the 20th century, grain ranches that had previously profited from wheat began to bankrupt and close; the original owners of the ranches soon died off, and the heirs deeded land to those who were seeking it; this era brought about a land boom

A real-estate bubble or property bubble (or housing bubble for residential markets) is a type of economic bubble that occurs periodically in local or global real-estate markets, and typically follow a land boom. A land boom is the rapid increase ...

, and the new fruit ranchers in the region made arable hundreds of thousands of acres through irrigation. However, the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act

The Chinese Exclusion Act was a United States federal law signed by President Chester A. Arthur on May 6, 1882, prohibiting all immigration of Chinese laborers for 10 years. The law excluded merchants, teachers, students, travelers, and diplom ...

in 1882 noticeably dampered the economic growth of Sacramento's agriculture. Despite the anti-Asian sentiment, all types of foreigners were drawn to the city starting in the 1890s, ranging from Europeans that had immigrated from Italy, Portugal, and Croatia

, image_flag = Flag of Croatia.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Croatia.svg

, anthem = "Lijepa naša domovino"("Our Beautiful Homeland")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capit ...

to Japanese, Korea

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republic o ...

n, Punjabi, and Filipino

Filipino may refer to:

* Something from or related to the Philippines

** Filipino language, standardized variety of 'Tagalog', the national language and one of the official languages of the Philippines.

** Filipinos, people who are citizens of th ...

arrivals.Avella, p. 77-78 Many of these immigrants aligned themselves with the local Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

.Avella, p. 78

Although schoolhouses had existed in Sacramento County since 1853, Sacramento High School

Sacramento Charter High School ("Sac High") is an independent public charter high school in the Oak Park neighborhood of Sacramento, California. Originally founded in 1856, Sacramento High is the second oldest public high school in California. I ...

, the city's first secondary education institution, was founded in 1856 and instructed students in courses ranging from core English and mathematics to astronomy and bookkeeping. The high school was moved to a permanent location in 1887 as Sacramento's population started to skyrocket, and the high school administration opened twelve elementary feeder schools across the city of Sacramento. Starting in 1894, in tandem with the early civil rights movement, individual schools in the city began to integrate.

World War I and the Prohibition – 1901 to 1930

Theautomobile

A car or automobile is a motor vehicle with Wheel, wheels. Most definitions of ''cars'' say that they run primarily on roads, Car seat, seat one to eight people, have four wheels, and mainly transport private transport#Personal transport, pe ...

was introduced to the city in 1900 through a local street fair; in 1903, the first car dealership opened, and the year after, twenty-seven Sacramentans owned cars. The number of automobile owners increased exponentially from that point. The advent of the automobile obsoleted careers involving horseback and overland wagon travel and decreased the importance of the steamboat

A steamboat is a boat that is marine propulsion, propelled primarily by marine steam engine, steam power, typically driving propellers or Paddle steamer, paddlewheels. Steamboats sometimes use the ship prefix, prefix designation SS, S.S. or S/S ...

and railroad industries.Avella, p. 89

A series of Progressive

Progressive may refer to:

Politics

* Progressivism, a political philosophy in support of social reform

** Progressivism in the United States, the political philosophy in the American context

* Progressive realism, an American foreign policy par ...

Sacramentan politicians rose to key positions in the city government, implementing various methods of reform. Mayor George H. Clark, Land's successor, worked to end illicit gambling activity in the city's poolhouses; he also passed a referendum that reformed the Sacramentan charter government, equalizing the political power of each of the city's wards so as to avoid dominance in wards that hosted a rapidly growing working class population. 1907 saw a breakage in the monopoly

A monopoly (from Greek language, Greek el, μόνος, mónos, single, alone, label=none and el, πωλεῖν, pōleîn, to sell, label=none), as described by Irving Fisher, is a market with the "absence of competition", creating a situati ...

that the Southern Pacific Railroad held over Sacramento when the second Western Pacific Railroad requested permission to construct yards in the city's vicinity, while women's rights activist L.G. Waterhouse, who headed the Sacramento Women's Suffrage Association, worked toward women's suffrage. Sacramentan women were granted the right to vote in 1911, nearly nine years prior to the passage of the nineteenth amendment that enforced this suffrage nationwide.

At the same time, the

At the same time, the Rancho Del Paso

Rancho Del Paso was a Ranchos of California, Mexican land grant in present-day Sacramento County, California, In 1844 by Governor Manuel Micheltorena, Captain John Sutter’s old friend, gave 44,000 acres to Elijah Grimes. Grimes called it the Ran ...

and Rancho San Juan Rancho San Juan was a Mexican land grant in present-day Sacramento County, California given in 1844 by Governor Manuel Micheltorena to Joel P. Dedmond. The grant extended east of Captain Eliab Grimes Rancho Del Paso along the north bank of the ...

Mexican land grants that encompassed much of the northern parts of the county were sold to the public; people who invested in county development would construct the settlement of Citrus Heights on the land designated as the grant; plans for communities like Orangevale, Carmichael, and Fair Oaks were set into motion to complement the city's reputation as a fruit production powerhouse.Avella, p. 81 The city began to expand exponentially after the Sacramento government convinced the residents of East Sacramento

East Sacramento (also known as East Sac) is a neighborhood in Sacramento, California, United States, that is east of downtown and midtown. East Sacramento is bounded by U.S. Route 50 to the south, Business Loop 80 to the west and north, Elvas Ave ...

and Oak Park to approve annexation. The three cities were officially joined in September 1911.Avella, p. 80 The first automobile-friendly settlement to be founded was North Sacramento

North Sacramento is a well-established community that is part of the city of Sacramento, California. It was a city from its incorporation in 1924 until it was merged (in a bitter election decided by 6 votes) in 1964 into the City of Sacramento. I ...

, which was bisected by Del Paso Boulevard.

Nearly 4,000 troops destined for battle in Europe's First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

had come from Sacramento and other cities within the county; of those 4,000, about 100 died. The coming of the war also sparked hysteria amongst the population, biasing them against Germans and concepts associated with Germany. Sacramento's Lutheran

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched th ...

churches began to preach in languages other than German. Additionally, a Council of Defense searched for and punished signs of disloyalty to the American cause.Avella, p. 82 City tensions increased with the bombing of the governor's mansion in 1917, and suspects affiliated with the Industrial Workers of the World

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), members of which are commonly termed "Wobblies", is an international labor union that was founded in Chicago in 1905. The origin of the nickname "Wobblies" is uncertain. IWW ideology combines genera ...

militant party were detained and jailed, although never convicted.Avella, p. 84 When the war ended in 1918, the city celebrated the return of the 363rd Infantry regiment of the 91st Division and the visit of president Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

, who arrived to advocate his League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

proposal in 1919 in the face of staunch opposition headed by Governor Johnson and ''Sacramento Bee

''The Sacramento Bee'' is a daily newspaper published in Sacramento, California, in the United States. Since its foundation in 1857, ''The Bee'' has become the largest newspaper in Sacramento, the fifth largest newspaper in California, and the 2 ...

'' editor Charles Kenny McClatchy

Charles Kenny McClatchy, better known as C. K. McClatchy (November 1, 1858 – April 27, 1936), was the editor of '' The Sacramento Bee'' and a founder of McClatchy Newspapers, the family-owned company that was forerunner to The McClatchy Com ...

.Avella, p. 84 The coming of the 1917 American intervention in World War I exponentially increased demand for Curtiss JN-4

The Curtiss JN "Jenny" was a series of biplanes built by the Curtiss Aeroplane Company of Hammondsport, New York, later the Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company. Although the Curtiss JN series was originally produced as a training aircraft for th ...

biplanes. A contract with the government led to the opening of Mather Air Force Base

Mather Air Force Base (Mather AFB) was a United States Air Force Base, which was closed in 1993 pursuant to a post-Cold War BRAC decision. It was located east of Sacramento, on the south side of U.S. Route 50 in Sacramento County, Californ ...

in the county, and Sacramento grew to rely on the biplanes for continued economic growth up until the end of the war. Surplus military equipment, including the biplanes, were put to use by the Sacramentan populace. In 1929, farmers in the Sacramento area experimented with crop seeding via aerial means; notably, Chinese revolutionary Sun Yatsen

Sun Yat-sen (; also known by Names of Sun Yat-sen, several other names; 12 November 1866 – 12 March 1925)Singtao daily. Saturday edition. 23 October 2010. section A18. Sun Yat-sen Xinhai revolution 100th anniversary edition . was a Chinese ...

, with assistance from Delta farmer Jack Chew, purchased ten surplus aircraft and held sessions for maneuver practice from a local alfalfa field with local Chinese pilots. A growing civilian fascination with aviation in the era was fed by the numerous air shows that were held around the Sacramento area.

In 1920, Sacramento adopted a new charter government that dictated the creation of nine positions on a new

In 1920, Sacramento adopted a new charter government that dictated the creation of nine positions on a new Sacramento City Council

The Sacramento City Council is the governing body of the city of Sacramento, California. The council holds regular meetings at Sacramento City Hall on Tuesdays at 6:00 pm, with exceptions for holidays and other special cases.

Sacramento's city co ...

along with a paid city manager position, which would be held by Illinois journalist Clyde Seavey after the initial rechartering of the government in 1911 that formed five elected nonpartisan commissioner positions failed to effectively serve the city. These actions restricted the power of the mayor and broke the working class' grip over city politics. Seavey pushed strongly for reform, rendering businesses related to clairvoyance nonviable and closing or refusing to license local saloons and poolrooms; Seavey consolidated civic departments to lower the city's budget and reinstated the chain gang

A chain gang or road gang is a group of prisoners chained together to perform menial or physically challenging work as a form of punishment. Such punishment might include repairing buildings, building roads, or clearing land. The system was no ...

punishment to deter crime.

In 1903 the Sacramento Solons

The Sacramento Solons were a minor league baseball team based in Sacramento, California. They played in the Pacific Coast League during several periods (1903, 1905, 1909–1914, 1918–1960, 1974–1976). The current Sacramento River Cats began pl ...

a minor league baseball team began to play. The Solons played intermittently in Sacramento between 1903 and 1976, with a continuous stretch between 1918 and 1960. After the end of the Sacramento Solons franchise in 1976, Sacramento went without a minor league baseball team until 2000 when the Sacramento River Cats

The Sacramento River Cats are a Minor League Baseball team of the Pacific Coast League (PCL) and are the Triple-A affiliate of the San Francisco Giants. Prior to 2015, the River Cats were the Triple-A affiliate of the Oakland Athletics for 15 yea ...

began playing at Raley Field

Sutter Health Park is the home ballpark of the Sacramento River Cats Minor League Baseball team, which is a member of the Pacific Coast League. Known as Raley Field from 2000 to 2019, the facility was built on the site of old warehouses and rail ...

in West Sacramento

West Sacramento (also known as West Sac) is a city in Yolo County, California, United States. The city is separated from Sacramento by the Sacramento River, which also separates Sacramento and Yolo counties. It is a fast-growing community; the p ...

.

The eighteenth Constitutional amendment initiated the Prohibition Era

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacturing, manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption ...

in the United States at the end of World War I. As Northern Californian vineyards were major producers of American wines, the significant loss in business forced many, including Sacramento's two largest vineyards, to close; the city was not sympathetic to either prohibition or the temperance movement, although elements of the temperance movement were noticeable in the Sacramento area. In addition, the river front city border with Yolo County

Yolo County (; Wintun: ''Yo-loy''), officially the County of Yolo, is a county located in the northern portion of the U.S. state of California. As of the 2020 census, the population was 216,403. Its county seat is Woodland.

Yolo County is incl ...

, known as the West End, devolved into a slum that was filled, notably, with speakeasies

A speakeasy, also called a blind pig or blind tiger, is an illicit establishment that sells alcoholic beverages, or a retro style bar that replicates aspects of historical speakeasies.

Speakeasy bars came into prominence in the United States d ...

, bordello